I recently had an article published in Power and Education that comes out of my PhD, here is the accepted version – if you need to reference if you can get a copy of the published version, which you can find here. This version may have some grammatical and/or referencing mistakes!

Abstract

This article approaches the question of how far critical pedagogy can be institutionalised through a series of historical and contemporary examples. Current debates concerned with the co-operative university are examined, as well as histories of independent working-class education and the free university movement. Throughout this history, critical pedagogy has occupied a difficult space in relation to higher education institutions, operating simultaneously against and beyond the academy. The Deweyian concept of ‘democratisation’ allows the institutionalisation of critical pedagogy to be considered as a process, which has never been and may never be achieved, but is nevertheless an ‘end-in-view’. The article concludes by offering the Lucas Plan as a model of radical trade unionism that could be applied to the democratisation of existing universities and the institutionalisation of critical pedagogy

Introduction

As political activists and critical pedagogues working ‘in, against and beyond’ universities in the UK, we are by now aware of the ways in which neoliberalism transforms and dominates society, its institutions and social relations (Mirowski, 2013; Davies, 2014; Brown, 2015). The term ‘critical pedagogy’ was coined and popularised by Henry Giroux in the 1970s, but has a genealogy that ‘extends back centuries’ (Amsler, 2013).

Today, more than two decades deep into a period of far-reaching reforms to higher education and the growth of academic capitalism, the idea of critical pedagogy seems to have acquired an aura as the obvious ‘alternative’ to all forms of commodified and marketized education. At the same time, depoliticised forms of ‘critical thinking’ have been integrated into the curricula of university programmes oriented towards shaping the ‘entrepreneurial’ student-subject. And yet, what it means to think, teach or ‘be’ critically, in theory and in practice is rarely articulated among university students or teachers. it is time, once again, to take stock. (Amsler, 2013, pp. 66-67).

The above quote notes critical pedagogy’s complex relationship with the university. The ‘in, against and beyond’ of critical pedagogy describes, respectively, attempts to: (1) bring political and social analysis into the classroom through critical-pedagogical techniques, in order to break through the commodification of higher education; (2) change the structure of higher education institutions within which such teaching takes place; and (3) look beyond the academy altogether to create radically different forms of higher education that are not answerable to the logic of the market (Cowden and Singh, 2013).

This paper will focus on some historical and contemporary examples of (2) and (3), to raise the question of how far critical pedagogy in these forms can be institutionalized. As Amsler points out, (1) often results in ‘depoliticised forms of critical thinking’. The pressures of marketisation not only make such consciousness raising extremely difficult, with students understandably wanting their £9000 degree to lead to a decent career, but in many cases this kind of critical pedagogy is all too easily recuperated into the marketized system as part of a university’s brand, as with Goldsmiths, University of London, for example. Furthermore, in terms of emancipatory research, the Research Excellence Framework (REF) pushes all knowledge production towards utilitarian ends, ultimately encouraging, at best, game-playing and cynicism, at worst, capture and monetisation within over-arching neoliberal objectives (Holmwood, 2011; Hammersley, 2014; Watermeyer, 2014). The 2016-17 Higher Education Bill proposes to consolidate the marketisation of higher education, firstly introducing ‘alternative providers’ to create a ‘quasi-market’, and secondly implementing the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), which John Holmwood (2015) has described as an ingenious ‘big data project’ designed to re-align higher education towards neoliberal socio-economic ends.

This paper explores the question of critical pedagogy’s institutionalisation through the concept of ‘democratisation’. For John Dewey, a key figure in the early history of critical pedagogy, institutions are ‘relatively fixed’, they are ‘a tough body of customs, ingrained habits of actions, organized and authorized standards and methods of procedure’ (Dewey, 2008, p. 153). Institutions should be analysed in terms of their function, and educational institutions should be critiqued according to how far they encourage what Dewey called ‘growth’, which is the ‘enlarging and enriching of experience’ (Ralston, 2010). For Dewey, life itself is educative, and experience is a process of problem solving that can be developed into more or less institutionalised forms of inquiry, such as science, morality and education. As ingrained social ‘habits’, institutions can be made more intelligent. As intelligence is the capacity to successfully deal with problems arising in experience, the intelligence of an institution can be judged on how far it frustrates or encourages the application of natural intelligence in dynamic problem-solving. Democracy, as ‘an ethical way of life’, is a way of organizing people that decentralises responsibility and control as much as possible while encouraging pluralism in points of view. Both aspects of democracy encourage growth, and should form the basis for any process of ‘democratisation’. ‘Democratisation’ is used instead of ‘democracy’ as the former is concerned with a process of transformation, rather than with a fixed ideal. For Bernstein (1983), ‘democratisation’ is more realistic, and ‘helps us to keep aware of the fact that, in all probability, there is no fixed, or final state of democracy’ (Bernstein, 1983).

In Deweyian terms, ‘democratisation’ is an ‘end-in-view’ (Dewey, 1916). Dewey argued that there was no such thing as an ‘end-in-itself’, just as it is obvious that there cannot be a ‘means-in-itself’. Instead, he proposed a ‘means-end continuum’, which from a pragmatic perspective means that all ends become means for further action, and means must be sometimes considered as ends, for example when new tools, concepts or theories are developed. For critical pedagogy, as an ‘end-in-view’, democratisation is both end and means. Critical pedagogy tends to separate the critique of neoliberalism and neoliberal education from critical-pedagogical practice. Many of theories of the latter are developed in contexts that are so different from the here and now that the recommendations seem utopian. The concept of democratisation changes the question from ‘what is wrong with the world and what should it be like?’ to ‘Where are we going and how do we get there?’ The former encourages disappointment, and what Dewey (1917) would call ‘consolation’ in theory, while the latter is explicitly oriented towards action. Democratisation allows us to be pragmatic, rather than idealistic. The ‘against and beyond’ thus describes a process rather than a dichotomy, and transforms critical pedagogy into an inquiry into the limits of its own institutionalization.

Against the neoliberal university

In response to the privatisation and marketisation of the public sector, many educational institutions have turned towards ‘co-operation’ as an alternative. Since 2008, 700 co-operative schools have been created in England (Woodin, 2015), with the Schools Co-operative Society now one of the ‘fastest growing networks of schools in the UK … dwarfing the academy chains more frequently mentioned in the press’ (Cook, 2013, p. 10). The co-operative movement is now considering how this success can be extended to higher education, with a new discourse around the ‘co-operative university’ emerging (Neary and Winn, 2016; Yeo, 2015; Somerville, 2014; Cook, 2013; Boden et al, 2012; Ridley-Duff, 2011). For many, the need to think about co-operative higher education is a direct result of marketisation, and co-operative universities are a way to protect ‘the idea of the university’, which is to say ‘higher education as a public good’ (Yeo, 2015; Holmwood, 2011b).

The co-operative university model seems to provide an excellent ‘end-in-view’ for democratisation. The 1995 ‘Statement of Cooperative Identity’ defines the core values of co-operatives as ‘self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity and solidarity’ (Woodin, 2015). Furthermore, two cooperative principles highly relevant to democratisation are ‘democratic member control’ and ‘member economic participation’. Democratic member control requires that members ‘activity participate in setting their policies’ and in decision making. Member economic participation requires that ‘at least part of the capital [of the cooperative] is the common property of the cooperative’. In terms of democratisation, the former principle would ensure that the people affected by decisions made by the institution are involved in the decision-making process, thus also must take responsibility for any decisions made, while the latter principle grounds this participatory process in concrete economic concerns, preventing this process from becoming a façade.

As well as cooperatives providing an attractive end-in-view for democratisation, the principle of the ‘autonomy and independence’ of cooperatives strikes a chord with the idea of academic freedom at the heart of modern universities. The UNESCO (1992) working document on ‘Academic Freedom and University Autonomy’ defines the latter as a ‘characteristic of the decision-making process’ of universities, and asserts that ‘each university must make its own decisions on matters related to knowledge, research, and teaching.’ Within actually existing universities, this does not translate to democratic structures of collegiality. Murray et al (2013, p. 8) draw attention to the way in which the concept of ‘academic freedom’ has been increasingly absorbed into an institutionalised view of autonomy:

The implication here appears to be that ‘academic freedom’ belongs to the university, not to the academic. Here and elsewhere it seems that there is a not-too-subtle redefinition by university managers of ‘academic freedom’ from meaning ‘freedom of academics from us’ to ‘freedom for us from everyone’. And this is taking place at a time of growing concern about whether real academic freedom is really being protected.

Cooperative universities, on the other hand, would democratise this relation, insisting on democratic and economic control by members, ensuring that autonomy is owned by members and materially linked to their academic freedom.

The problematic link between institutional autonomy and academic freedom points to governance as a key site of struggle for democratisation. For Boden et al (2012), the separation of ownership and control in ‘quasi-private’ universities, in particular post-92 universities, has led to serious issues in governance. The ‘fuzzy’ question of who owns these ‘quasi-private’ institutions, combined with managerial approaches that distrust collegiality and collective bargaining traditions, both result in ‘managerial predation’ on the part of Vice-Chancellors. This can be evidenced the astonishing increases in Vice-Chancellor salaries: in 2016, their average salary was £272,432, with the maximum being £516,000 (University of Salford). The average pay increase for vice-chancellors between 2013/14 and 2014/15 was 3% (UCU, 2016b), compared with a real terms loss of 14.5% since 2009 for academics (UCU, 2016c).

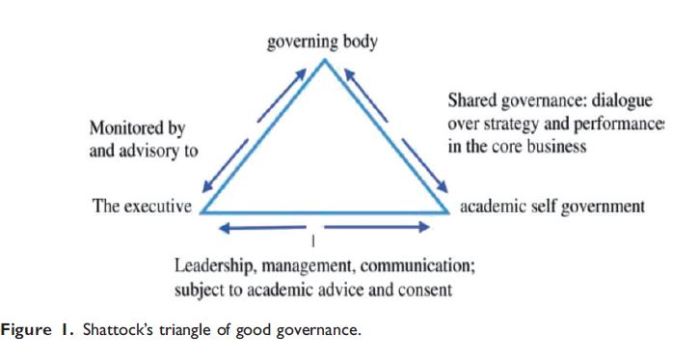

Shattock’s (2012) triangle of good governance allows us to see the problem of governance in universities more clearly:

Within neoliberal universities, i.e. universities that have become victim to ‘new managerialism’ as a result of neoliberal reforms (Bacon, 2014; Deem et al, 2007), this triangle breaks down at two points. Firstly, governing bodies ‘don’t always assert themselves’ and have ‘great difficulty in challenging their executives’ (Shattock, 2012, p. 59). Furthermore, governing bodies tend to be made up of ‘part-time amateurs largely unfamiliar with the organisation’s culture’ who ‘without specialised knowledge … tend to dwell on the more familiar realms of operations, finance and investment, usually to the neglect of the institution’s core business’ (Taylor et al, 1996, p. 3). Secondly, academic self-government has been replaced by Senior Management Teams (SMTs); senior colleagues transformed into line managers, directly answerable to the executive. What collegial behaviour remains is skewed by targets and the measurement of outputs within regimes of performance management. Thus, the system of ‘checks and balances’ that should underpin good governance in universities cannot function, resulting in not just managerial predation, but also excessive risk taking with what still remain public institutions.

Boden et al (2012) suggest the idea of a ‘trust university’, based on the John Lewis Partnership (JLP) model, as a solution to this governance problem, while at the same time offering a means of defending the idea of the university in a concrete way. In a ‘trust university’, the combined assets of the institution would be put into a ‘non-revocable trust’, which would mean that they could not be sold off for the self-interest of any member of the institution. This move is particularly important as the HE sector becomes marketised, as this would ensure that public assets, paid for by taxpayers, are protected. As with JLP, employees can then be made beneficiaries, effectively becoming ‘partners’, with rights to influence decision making and any profits either put back into the company (which would be most appropriate for a ‘quasi-public’ institution) or redistributed as an annual bonus. The public interest and democratic structure of the ‘trust university’ can then be enshrined in a charter. The first article of JLP’s trust deed, for example, outlines the purpose of the company: ‘To ensure happiness of all its members through their worthwhile and satisfying employment in a successful business’ (in Boden et al, 2012, p. 21).

For critics of this model, however, the trust university does not in fact overcome the deep problems of governance caused by the separation of ownership and control. In a trust university, corporate governance would not necessarily change, and workers would not necessarily be directly involved in decision making. For Somerville (2014, p. 4 – 5), the trust university is ‘way short of being a member controlled body [as] there is no challenge to either the capitalist wage or to the internal management hierarchy’. Cook (2013) agrees, pointing out that the trust university is a ‘sub-optimal’ model of co-operation, as the division of labour is retained and market pressures still encourage efficiency over democracy. Even at Mondragon University, arguably the most successful co-operative university in existence, the reality and myth of worker participation have diverged significantly. For Kasmir (1996), who conducted a deep ethnographic study of Mondragon, the myth and the overwhelming desire to believe in co-operative education hides evidence of suppressed dissatisfaction among workers there. Kasmir describes how the myth of co-operation creates an a-political system where workers are not actively engaged in holding governing process to account, and workers are manipulated by managers through nationalist ideologies. Mondragon teaches us of the importance of politics, the necessary role of organization, and the continuing value of syndicates and unions for transforming the workplace.

The Lincoln Social Science Centre (SSC) represents an attempt to democratise higher education by building a new university on cooperative principles. It is also an explicit attempt to institutionalise critical pedagogy within its foundations. The SSC was ‘conceived in response to the UK Coalition government’s changes to higher education funding which involved an increase in student fees up to £9,000 and defunding of teaching in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences’ (Neary and Winn, 2016, p. 3). In their own words, the SSC (2013)

Organises free higher education in Lincoln and is run by its members. The SSC is a co-operative and was formally constituted in May 2011 with help from the local Co-operative Development Agency. There is no fee for learning or teaching, but most members voluntarily contribute to the Centre either financially or with their time. No one at the Centre receives a salary and all contributions are used to run the SSC. When students leave the SSC they will receive an award at higher education level. This award will be recognized and validated by the scholars who make up the SSC, as well as by our associate external members – academics around the world who act as our expert reviewers. The SSC has no formal connection with any higher education institution, but attempts to work closely with like-minded organizations in the city. We currently have twenty-five members and are actively recruiting for this year’s programmes.

One of these programmes is the introductory course ‘Social Science Imagination’, which is for ‘anyone who wants to learn more about how the social world works and how we can change it, with the help of social science’. In 2016/17, it was decided by participants that the course ‘will focus on ‘Brexit, unemployment, the concerns of rural communities and the government’s campaign against radical extremism’. With the SSC, we can see critical pedagogy in both its structure and practice.

Although the SSC has never had a significant number of students, at least compared to traditional higher education institutions, it has managed to survive since 2011 and retain its cooperative structure. The Higher Education Bill 2016-17 poses an interesting dilemma for the SSC:

A key objective in these government reforms is to open the sector to ‘alternative providers’. Up until now, this has been interpreted as providing a space for market-based provision, aaccentuating the principle of the policy. Our point is that it opens up a ‘crack’ for a real alternative, neither private nor public, that undermines the policy and resists the logic of the capitalist state on which it is premised. (Neary and Winn, 2016, p. 3)

Although this statement seems optimistic regarding the HE Bill, it is not clear whether the SSC would aim to become formally recognised as a ‘university’ with degree awarding powers (DAPs), or continue to exist outside the system. This reveals a tension at the heart of the project, described by Joss Winn (2015) as the ‘dialectic’ of the cooperative form within capitalism. This dialectic is enacted as a ‘prefigurative politics’, in which the ‘social relations, dream-making, culture and human experience that are the ultimate goal’ are embodied in ongoing political practice. As its negative, the cooperative form confronts the capitalist system with an ‘immanent critique’, revealing ‘both the reality and the ideals of capitalist society’ and their historically determinate nature. This, however, is a difficult dialectic within which to maintain the SSC. If it chooses to be absorbed within the ‘quasi-market’ of neoliberal higher education, becoming fully institutionalised, for the same reasons as critical pedagogy ‘within’ the neoliberal university, it is unlikely to be able to maintain its cooperative structure and practice, at least in such a pure form. But if it remains entirely outside the system, as it is now, the force of the SSC’s immanent critique will be severely limited.

This problem of the institutionalisation of critical pedagogy also runs through the history of Independent Working Class Education (IWCE). The SSC ‘recognises and builds on a long tradition of working class, self-managed, alternative, open and radical education’ (Neary and Winn, 2016, p. 28), a tradition that can be traced back to the correspondence societies of the late 18th century. As described by E. P. Thompson (1963) in The Making of the English Working Class, correspondence societies were informal gatherings of artisans and other working people who met to read aloud and discuss the latest radical pamphlets, Tom Paine’s The Rights of Man being a popular example. In contrast to the ‘bourgeois’ public sphere (Habermas et al, 1964), these crucial institutions of its ‘plebian’ (Fraser, 1990; Negt and Kluge, 1993) counterpart were explicitly political and radically democratic, placing no limitations on membership. Thomas Hardy (in Thompson, 1963, p. 151), argued that the purpose of the Sheffield Correspondence Society was

To enlighten the people, to show the people the reason, the ground of all their sufferings; when a man works hard for thirteen or fourteen hours of the day, the week through, and is not able to maintain his family; that is what I understood of it; to show the people the ground of this; why they were not able.

We can see here that the earliest forms of IWCE are very much early examples of critical pedagogy. They are also very Deweyian. Inquiry moves from the concrete every day to the reconstruction of problematic situations through reflection and discussion. The results of inquiry then form the basis for action, for example in the production of a pamphlet or in the organisation of a public meeting. These may not seem very radical today, but in the late 18th century even such minor actions were considered illegal, and could be punished severely as intention to commit treason.

The IWCE tradition continued with the Chartists in their critique of ‘useful knowledge’. The idea of ‘useful knowledge’ descended from the middle and upper classes, as an attempt to civilise the increasingly unruly and independent working class, which were beginning to be perceived as dangerous. The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, for example, was a mid-19th century organisation that simplified scientific texts for a wide audience, with the explicit purpose of neutralising radical pamphlets and newspapers (Johnson, 1988). In contrast to such uses of knowledge as ‘subjection’, Chartist really useful knowledge ‘served practical ends, ends that is for the knower’ (Johnson, 1988, p. 21). For 19th century radicals, ‘practical’ meant learning how to change the world through understanding the ‘conditions of life’ and real problems faced by real people. This knowledge, according to George Jacob Holyoake, ‘lies everywhere to hand for those who observe and think’, and because its purpose was the emancipation of the working class, was inherently partisan (in Johnson, 1988, p. 18). Again, we can see here an early version of critical pedagogy, especially in its emphasis on everyday problems that through reflection become the vehicle for emancipatory knowledge. The partisan emphasis also echoes Dewey’s concern for the unity of means and ends, where democratic knowledge is knowledge that is used by those who created, not for the profit of others who appropriate it or a means for subjection (Dewey, 1935).

The debate between useful and really useful knowledge initiates an antagonism between formal and information education that lasts right up until the present day, which is also a history of attempts to institutionalise critical pedagogy. This antagonism came to a head at the beginning of the 20th century at Ruskin College, an early version of the university extension courses that became popular in the mid-20th century (for which E. P. Thompson and Raymond Williams taught). The impetus behind Ruskin College was the same as that of ‘useful knowledge’: to provide an education for the working class that show them the ‘correct’ way to think, so that they would become amenable to and aspire to middle class ideas, rather than the revolutionary ideas coming at that time from European Marxism. But again, the already radicalised working class students at Ruskin rejected these attempts at pacification, and demanded a more radical curriculum. This dispute reached a crisis point in 1908 when the Marxist students formed the Plebs League, went on ‘strike’ and eventually left Ruskin to set up their own independent working class college, the Central Labour College in Oxford (Waugh, 2009). This college was initially supported by the National Union of Railwaymen and later by the Trades Union Congress, and soon grew into a network of independent labour colleges under the umbrella organisation the National Council of Labour Colleges (NCLC). After the Ruskin strike, the adult education movement split into independent (NCLC) and paternalistic forms, the latter represented by the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA), which set up university extension courses all over Britain. The NCLC, due to a lack of funding and a deep suspicion of state intervention eventually collapsed into the trade union movement, which according to Armstrong (1988) had itself had become ‘right-wing’ during the period of labour-capital compromise coming out of the Second World War.

This history of IWCE opens up once again the question of the desirability of institutionalisation. Institutionalisation is attractive because the resources and longevity of established institutions can be, at least in principle, appropriated for radical ends. But for IWCE, institutionalisation was a primary danger, representing on the one hand appropriation by the middle class and on the other increased state control. For IWCE, institutionalisation came to represent a fundamental threat to independence. But as Armstrong (1988) argues, this fear of institutionalisation also undermined any possibility for such independent forms to become sustainable; we can see the history of IWCE as a history of failed attempts to sustain a movement. With IWCE, we see once again the dialectic of institutionalisation and independence that is at the heart of critical pedagogical practice. For Armstrong, this dialectic must today be once again raised to consciousness if any attempt to rescue IWCE is undertaken, primarily through an understanding of the Gramscian concept of ‘hegemony’ (the way that institutions reproduce the class form of capitalist society), and incorporating this into the theoretical foundations of IWCE. For Waugh (2016, p. 20), IWCE practitioners should become ‘midwives’, ‘working with people to help them level up their own insights into a consistent socialist consciousness and capacity to act’.

In the 1960s, the Free University movement re-enacted this dialectic of institutionalisation, but from the perspective of middle class intellectuals. According to the Winter Catalogue of 1966, the Free University of New York (FUNY) was

Forged in response to the intellectual bankruptcy and spiritual emptiness of the American educational establishment. It seeks to develop the concepts necessary to comprehend the events of this century and the memory of one’s own life within it, to examine artistic expression and promote the social integrity and commitment from which scholars usually stand aloof. (in Jakobsen, 2013, p. 10)

Joseph Berke was a founding member of both FUNY and the Anti-university, which was based in London, and very influenced by the anti-psychiatry of R. D. Laing. The Anti-university emerged out of the Dialectics of Liberation Congress in 1967, which featured key anti-psychiatrists as well as leading critical theorists, such as Herbert Marcuse. ‘Deinstitutionalisation’ was, therefore, a key concept of the ‘Anti-university’. which involved a paradoxical attempt to create a new institution with the same form as the one it is meant to replace. For Berke, ‘institutions must be destroyed and rebuilt in our own terms’, and ‘in the process of making an institution we deinstitutionalise ourselves’ (in Jakobsen, p. 9). This position, however, created irresolvable contradictions within the Anti-university, which had adopted a conservative organisational structure and pedagogical approach, leading to rebellion on the part of radical students attending Anti-university courses. These students challenged all hierarchy represented by the ‘ad-hoc coordination committee’ who directed the anti-university, shouting slogans such as ‘pay the students charge the teachers’, pushing the principles of the anti-institution to its limits. Eventually what little structure there was dissolved into dispersed and permanently changing courses held in people’s flats, cafés and pubs. As Shalmy (2016) concludes:

The staff and visiting lecturers somehow all fell out, the administration was chaotic and a lack of funding eventually led to their eviction from the building on Rivington Street. Despite everyone’s best efforts, the Antiuniversity did not revolutionise academia and create a new world order, but it left a legacy. (Shalmy, 2016, n.p.)

This legacy was resuscitated during the student movement of 2010, the same movement that produced the SSC, seeing many other free universities conceived in response to the UK Coalition government’s changes to higher education funding. What linked these more recent examples with the Anti-university and Free University of New York was a shared sympathy with situationism, an avant-garde political, student and art movement that emerged in 1950s Europe, which came to prominence during the 1968 general strike in Paris (Ross, 2004). A key text of this period was Alexander Trocchi’s (1963) A Revolutionary Proposal: Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds, which called for the creation of a ‘spontaneous university’. According to Trocchi, the spontaneous university should take the form of a ‘cultural jam session’, and be situated away from the city, by a river ideally. Politically, the spontaneous university can be said to be utopian, in that it seeks to re-imagine society and the people themselves in a bubble that is at once within and outside society. Crucially, the spontaneous university should also be:

An international organization with branch universities near the capital cities of every country in the world. It will be autonomous, unpolitical, economically independent. Membership in one branch (as teacher or student) will entitle one to membership in all branches, and travel to and residence in foreign branches will be energetically encouraged … Each branch of the spontaneous university will be the nucleus of an experimental town to which all kinds of people will be attracted for shorter or longer periods of time and from which, if we are successful, they will derive a renewed and infectious sense of life. We envisage an organization whose structure and mechanisms are infinitely elastic; we see it as the gradual crystallization of a regenerative cultural force, a perpetual brainwave, creative intelligence everywhere recognizing and affirming its own involvement. (Trocchi, 1963, n.p.)

We see here not only the dialectic of institutionalisation, but also an early example of Winn’s ‘prefigurative politics’.

The ‘spontaneous university’ also establishes a strain of ‘horizontalism’ that runs through the Free University movement, becoming so important in the 2010 student movement. Horizontalism, as described in protean form by Trocchi, is a form of organisation that is fundamentally generative and creative, as well as ‘prefigurative’. Within horizontalist organisations, the controlling idea is actualized in concrete attempts at institutionalisation, but is not exhausted through this process. Each institution is autonomous, but supported and nourished by this controlling idea. We see this explicitly in the self-description of The University for Strategic Optimism (2011):

The University for Strategic Optimism [UfSO] is a nomadic university with a transitory campus, based on the principle of free and open education, a return of politics for the public, and the politicisation of public space.

The UfSO encouraged other groups of activists to set up their own campuses wherever they liked, or steal and re-use any of the theories, analyses or techniques that had been developed through ongoing political action. In what was to become an influential use of ‘flashmobbing’, the UfSO temporarily occupied a Lloyds’ Bank high street branch in Central London, turning it into a ‘transitory campus’ and recording an impromptu lecture that went viral on the internet. We see here also how the controlling idea, ‘free and open education’, along with the subsidiary aims, are realized but not exhausted in such transitory campuses.

The contemporary concept of ‘horizontalism’ also derives from the ‘alter-globalisation’ movement, in particular from the Zapatistas of Chiapas, Mexico, and is a translation from the original and indigenous concept ‘horizontalidad’. For Marina Sitrin (2006, p. vi-vii)

Horizontalidad does not just imply a flat plane for organizing, or nonhierarchical relationships in which people no longer make decisions for others. It is a positive word that implies the use of direct democracy and the striving for consensus, processes in which everyone is heard and new relationships are created. Horizontalidad is a new way of relating, based in affective politics, and against all of the implications of “isms.”

The idea of democracy as a process, beyond one person one vote, or the ‘tyranny of the majority’, has clear affinities with Deweyian democratisation. Instead of simply voting on issues, horizontalist organisation is committed to ‘consensus’, which means that issues are discussed until a consensus is reached. Within the Occupy movement, an embodiment of horizontalist organisation, meetings would go on for hours, sometimes even days (Marcus, 2012). Although exhausting, this commitment to democracy as a process is clearly also itself a process of mutual education, a tradition that we have already seen goes back to the correspondence societies of the 18th century, and comes close to Dewey’s idea of ‘democracy as a way of life’. Although horizontalism meets the same ‘dilemma’ of institutionalisation that runs through the other examples, and repeats many of the mistakes of the 1960s, with ‘leaderless politics’ in fact leading to informal domination and bullying, there does seem to be a consensus emerging that decentralization must be an essential component of contemporary forms of extra-parliamentary organisation (Bailey, 2012).

Our last example, by reinventing the Anti-university for the 21st century, seems to learn from all the traditions we have looked at so far. The contemporary Anti-university builds on the concept of the ‘organised network’ (Rossiter, 2006). Organised networks recognise the need for face-to-face organisation alongside online communication and networks, taking seriously the social basis of sustainability:

In order for networks to organize mobile information in strategic ways that address the issues of scale and sustainability, a degree of hierarchization, if not centralization, is required. (Rossiter, 2006, pp. 205-8)

The Anti-university encourages groups of activists based in any location across the world (although mainly in the UK) to organize events under the Anti-university banner. These events all take place within a week, and are organized and advertised centrally through an attractive and cleverly designed website. In 2016, events included

A lecture, a round table discussion, a gallery tour, an interruption, a presentation, a screening, a public reading, a practical workshop, a walking tour … While everyone worked under the Antiuniversity Now banner, most people didn’t know each other and we, the three co-organisers, never met most of the hosts. In fact, we never imagined that so many people would even hear about our project, never mind put all that time and effort into planning so many events. (Shalmy, 2016)

The Anti-university model was a great success, with over 60 events organised by 90 hosts and attended by over 1200 people. The model incorporates the ‘deinstitutionalisation’ of the original Anti-university, but adopts a more sustainable approach, using internet and social media technology to create an organized network that exists for as long as it can without exhausting itself, and lives to be repeated in the future. The contemporary Anti-university is also more socially open that the original version, with many events resembling the radically democratic and inquiry based discussions of correspondence societies.

This section has discussed some key examples of critical pedagogy that attempt to deal with the question of institutionalisation in practice. Any attempt to create such practices today must learn from the fact that this is a history of failure, but also realise that failure is a necessary component of democratisation. Democratisation must be pragmatic, it is a process and relies on a certain amount of optimism. Democracy is not something that can ever be achieved, but rather something that must be striven for and realized in all our strivings. Dewey’s (1938) argument with Marxism hinged on this point. He felt that Marxism, represented by Trotsky in his public debate with Dewey, deduced the means, violent revolution, from an end, socialism, that was itself based on a deterministic theory of history. For Dewey, the means must be continuous with the end, and then end must be worked out in practice. Democratisation, as both means and end, cannot decide the specific form that institutionalisation may take. The history of critical pedagogical practice provides both lessons as to means that can be applied and to formal characteristics that can be selected in order to shape its instructional structures. The analysis in this section points to the co-operative form as an excellent institutional basis for critical pedagogy, having a well-developed controlling idea in its principles of co-operation, as well as a rich and successful history of sustainable yet radical examples. The idea of a ‘secondary cooperative’ also provides flexibility, solidarity and resources through a centralized network of primary cooperatives (Ridley-Duff, 2011).

Against the neoliberal university

As indicated in the previous section, the co-operative form seems to present the most appropriate model for the institutionalisation of critical pedagogy. Democratisation, however, dictates that the co-operative form should not be posited as an abstract end, but as an end-in-view, to be realised in critical pedagogical practice. This is all the more important today as neoliberalism seeks to replace the value and practice of co-operation with those of individualism and competition. As Cook (2013, p. 43) argues, ‘cooperation is fundamentally as educative process’, which is why ‘cooperative education’ has always been both a core principle and fundamentally important practice in the history of the cooperative movement. For Dewey also, cooperation is a habit that we learn and develop through practice, and the best way to learn is to try things out (Bohman, 2010). Trade unionism, as the historical struggle of workers to learn to cooperate with the aim of democratising society, presents a possible critical-pedagogical mechanism for the realization of the cooperative university. To provide such a mechanism, however, trade unionism will need to move from being a defense of existing industrial relations to a form of creative inquiry into new possibilities for democratic worker control.

According to Hyman (2001), the history of British capitalism is distinctive in that it never had to deal with social revolutions, as in France for example. This has meant that the two antagonistic forces of labour and capitalist management gradually adapted to each other, with employers reaching a grudging acceptance of the functions of trade unions, and the latter settling for ‘a fair days pay for a fair days work’. In contrast to continental labour movements, British unionism has been historically anti-intellectual and has largely resisted total co-option by far-left parties such as the Communist Party. British trade unions have by and large ‘accepted and adapted to existing social and economic conditions’ and are resigned to protecting terms and conditions for workers within this system (Hyman, 2001, p. 68). The tradition of ‘free collective bargaining’ in the UK has also meant that the gains of trade unions have never been fixed at a wider political level. This means that terms and conditions are more sensitive to changes in political leadership and economic turbulence, exacerbating the mostly defensive posture of trade unions as they spend most of the time ‘firefighting’.

After the Second World War, industrial relations in the UK experienced a period of relative stability. This was because trade unions had had ‘a good war’, playing a key role in militarisation and managing the war economy, and both Labour and Conservative governments were happy to involve trade unions in the post-war reconstruction of British society (Undy, 2013). But after the ‘winter of discontent’ in the late 1970s, where trade unions (in particular the miners) confronted the Labour government at the time who wanted to control spiraling inflation through caps on pay rises (thus betraying the ‘social contract’ that had been established between the TUC and government), resulting in highly controversial strikes by gravediggers and waste collectors, trade unions in Britain lost large sections of support within the wider public. This loss of support was capitalised on by Thatcher in 1979, who rose to power through supply-side economic policy, which also had the desired secondary effect of crushing union strength through deregulation and mass unemployment. The Conservative leadership also introduced many anti-trade union policies in subsequent years, including laws against secondary picketing, ‘closed shops’ (where all new employees must also be trade union members), and the involvement of trade unions in the highest levels of industrial decision making (Undy, 2013)

Today trade union membership is at its lowest since 1995, with 6.5 million workers in trade unions, 24.7% of the population (Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, 2016). This is a long way from the peak of trade union membership in 1979, when 13 million workers were members of a trade union. The decline in trade union strength continued after Thatcher, with New Labour claiming to be supportive of trade unions while at the same time furthering the deregulation and modernisation of the British economy which started in the 1980s. The biggest challenge facing trade unions today, aside from this drop in membership, is the changing state of the UK workforce.

The 2013 Workplace Employment Relations Survey (WERS) ‘indicates that the use of fixed-term or temporary contracts grew in both the public and private sectors with five or more employees between 2004 and 2011. Their use rose from 51 to 53 per cent of in the private sector and from 17 to 21 per cent in the public sector’ (Hudson, 2014, p. 7).

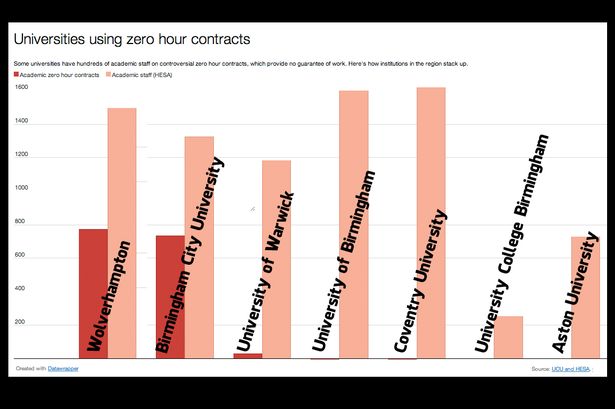

In higher education, 53.6% of all academic staff are on insecure contracts, and the University and Colleges Union (UCU) have been engaged in an effective campaign fighting casualisation which has resulted in many institutions moving away from the use of insecure employment contracts, as well as forcing a culture shift within the higher education sector as a whole (UCU, 2016). The effectiveness of UCU’s campaign is an example of the move towards an ‘organisational’ model of trade union strategy, which is more activist and grass-roots focused than the previous ‘partnership’ strategy (which characterised the ‘golden age’ of industrial relations, where unions worked together with management).

This move towards an organisation model of trade union strategy, as well as efforts to organize precarious workers, can be complimented by an even more radical form of grass-roots activism. In 1972, in response to mass redundancies in their workplace and an ineffective trade union apparatus, the Lucas Aerospace Combine Committee produced their ‘Corporate Plan: A Contingency Strategy as a Positive Alternative to Recession and Redundancies’, now simply known as the ‘Lucas Plan’. In response to a questionnaire distributed by the Combine to Lucas Aerospace workers, 150 socially useful products were suggested. Among those selected for further research were green innovations decades ahead of their time, such as ‘heat pumps, solar cell technology, wind turbines and fuel cell technology’, as well as ‘a new hybrid power pack for motor vehicles and road-rail vehicles’ (Salisbury, 2016). Although the Plan was rejected ‘out of hand’ by Lucas Aerospace management, the inquiry was itself as important as the stated aims of saving jobs and creating ‘socially useful’ products:

Perhaps the most significant feature of the corporate Plan is that trade unionists are attempting to transcend the narrow economism which has characterized trade union activity in the past and expand out demands to the extent of questioning the products on which we work and the way in which we work upon them. This questioning of basic assumptions about what should be produced and how it should be produced is one that is likely to grow in momentum. (Lucas Aerospace Combine Shop Stewards Committee, 1976, p. 9)

This quote, taken from the summary of the alternative corporate plan, indicates the Combine’s conscious attempt to reinvent trade union activism through democratisation. It also points to an awareness that it is this radical inquiry into alternatives, rather than any concrete achievement of socially useful production, that would survive and influence later generations.

As Mike Cooley (2016, p. 139), a key contributor to the original Lucas Plan, later reflected:

On the front page of the now famous Lucas Worker’s Plan for Socially Useful Production there is the statement that ‘there cannot be islands of social responsibility in a sea of depravity’. Lucas workers themselves never believed that it would be possible to establish in Lucas Aerospace alone the right to produce socially useful products … What the Lucas workers did was to embark on an exemplary project which would enflame the imagination of others. To do so, they realized that it was necessary to demonstrate in a very practical and direct way the creative power of ‘ordinary people’.

What Cooley and the other Lucas workers discovered, alongside Dewey, is that inquiry is the key to learning how to cooperate. Inquiry is the essential mechanism of democratisation that builds both consciousness and knowledge, both required for the institutionalisation of critical pedagogy. By focusing on ‘socially useful production’, the Combine also expanded and connected this process of democratisation to include the wider social context beyond the factory. An inquiry into ‘socially useful’ higher education would provide a much more effective way to anchor universities to the wider social context than the concept of a ‘public university’, a concept which can be seen as both conservative (looking back to a non-existent 1950s golden age) and ambiguous (as universities are ‘quasi-private’). Democratisation, as inquiry into the social function of universities, would also provide a way of connecting issues of marketisation to wider social struggles and members of the community who may otherwise not be invested in the fate of higher education.

Conclusion

This article has approached the question of how far critical pedagogy can be institutionalised through a series of historical and contemporary examples. Cooperatives seem to suggest the most appropriate form of institutionalisation, as democracy is not just a key cooperative principle but also enshrined in the cooperative form through worker control and ownership. As the longevity of the Lincoln Social Science Centre shows, cooperatives do not necessarily have to mimic the unwieldy and expensive structures of traditional universities, and can operate more like the ‘anti-institutions’ of the Free University movement. Secondary cooperatives also offer the kind of ‘organised networks’ that are a key innovation of contemporary free universities. By remaining in a utopian, or ‘prefigurative’ space, however, alternative institutions ‘outside’ the academy are severely limited in their capacity to democratise higher education. Within a post-Higher Education Bill marketized sector, cooperative universities face a difficult choice of becoming ‘alternative providers’, being subject to market forces and pressures that would inevitably undermine the radical potential of the cooperative form, or remaining aloof, relying on the unsustainable free time of academics and fluctuations of interest on the part of the public.

Democratisation through trade union activism, converting existing universities to the cooperative form, is a much more exciting possibility, but perhaps a more daunting prospect. Trade union structures already exist, providing much needed support and sustainability for attempts to democratise higher education, but ironically the institutionalisation of trade unionism leads to a conservativism in industrial strategy. Trade unions are still primarily concerned with protecting existing conditions and relations, and would see democratisation as outside traditional bargaining machinery. However, as the Lucas Plan has shown, worker’s inquiry, as a form of both critical pedagogy and democratisation, is an alternative trade union strategy that is effective in both creating solidarity in the workplace and with the wider public. In higher education trade unionism, this potential for building broad based support alongside other public sector workers is crucial for creating leverage in the fight against privatization and marketisation, and is also more likely to appeal to a new, non-traditional membership of casualised and migrant workers. The Lucas Plan suggests that through inquiries into alternative corporate plans existing union structures can be democratised alongside the university.

References

Amsler, S. (2013) ‘Criticality, Pedagogy and the Promises of Radical Democratic Education’. In Cowden, S. and Singh, G. (eds.) Acts of Knowing: Critical Pedagogy In, Against and Beyond the University. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 61 – 85

Armstrong, P. F. (1988) ‘The Long Search for the Working Class: Socialism and the Education of Adults, 1850-1930’. In Tom Lovett (ed.) Radical Approaches to Adult Education: A Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 35 – 59

Bacon, E. (2014) ‘Neo-collegiality: Restoring Academic Engagement in the Managerial University’. The Leadership Foundation for Higher Education. [Online] Available from: http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/11493/. Last accessed: 29/11/2016

Bailey, D. (2012) ‘#Occupy: Strategic Dilemmas, Lessons Learned?’. Journal of Critical Globalisation Studies 5, pp. 138 – 142

Bernstein, P. (1983) Workplace Democratisation: Its Internal Dynamics. New Brunswick: Transaction Books

Boden, R., Ciancenelli, P., and Wright, S. (2012) ‘Trust Universities: Governance for Post-Capitalist Futures’. Journal for Co-operative Studies 45(2), pp. 16 – 24

Brown, W. (2015) Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Cambridge: Zone Books

Cook, D. (2013) Realising the Co-operative University: A Consultancy Report for the Co-operative College. [Online] Available from: http://josswinn.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/realising-the-co-operative-university-for-disemmination.pdf Last accessed: 20/07/2016

Cooley, M. (2016) Architect or Bee? The Human Price of Technology. Nottingham: Spokesman.

Cowden, S. and Singh, G. (2013). Acts of Knowing: Critical Pedagogy In, Against and Beyond the University. London: Bloomsbury

Davies, W. (2014) The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty and the Logic of Competition. London: SAGE

Deem, R., Hillyard, S. and Reed, M. (2007) Knowledge, Higher Education, and the New Managerialism: The Changing Management of UK Universities. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (2016). Trade Union Membership 2015. [Online] Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/trade-union-statistics. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

Dewey, J. (1916) ‘Aims in Education’, in Hickman, L. A. and Alexander, T. M. (eds.) The Essential Dewey Volume 1: Pragmatism, Education and Democracy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 250 – 257

Dewey, J. (1917) ‘The Need for a Recovery of Philosophy’, in Hickman, L. A. and Alexander, T. M. (eds.) The Essential Dewey Volume 1: Pragmatism, Education and Democracy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 46 – 71

Dewey, J. (1927) ‘The Fruits of Nationalism’, in Boyston, J. A. (ed.) The Later Works of John Dewey, Volume 3, 1925 – 1953. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, pp. 152 – 158

Dewey, J. (1935) ‘Renascent Liberalism’, in Hickman, L. A. and Alexander, T. M. (eds.) The Essential Dewey Volume 1: Pragmatism, Education and Democracy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 323 – 336

Dewey, J. (1938) ‘Means and Ends: Their Interdependence, and Leon Trotsky’s Essay on ‘Their Morals and Ours’, in Morris, D. and Shapiro, I. (Eds) John Dewey: The Political Writings. Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company Inc., pp. 230 – 234

Dewey, J. (1939) ‘Creative Democracy: The Task Before Us’, in Hickman, L. A. and Alexander, T. M. (eds.) The Essential Dewey Volume 1: Pragmatism, Education and Democracy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 340 – 343

Fraser, N. (1990) ‘Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy’. Social Text 25/26, pp. 56 – 80

Habermas, J., Lennox, S. and Lennox, F. (1964) ‘The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article’. New German Critique 3, pp. 49 – 55

Hammersley, M. (2014) ‘The Perils of ‘Impact’ for Academic Social Science’. Contemporary Social Science 9(3), pp. 345 – 355

Holmwood, J. (2011) ‘Sociology After Fordism: Prospects and Problems’. European Journal of Social Theory 14, pp. 537 – 556

Holmwood, J. (2011b) ‘The Idea of a Public University’, in Holmwood, J. (ed.) A Manifesto for the Public University. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 12 – 26

Holmwood, J. (2015) Slouching Towards the Market: The New Green Paper for Higher Education Part II. [Online] Available from: http://publicuniversity.org.uk/2015/11/08/slouching-toward-the-market-the-new-green-paper-for-higher-education-part-ii/. Last accessed: 06/09/16

Hudson, M. (2014) Casualisation and Low Pay: A Report for the TUC. [Online] Available from: http://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Casualisationandlowpay.docx. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

Hyman, R. (2001) Understanding European Trade Unionism: Between Market, Class and Society. London: SAGE

Jakobsen, J. (2013) Antiuniversity of London: Antihistory Tabloid. [Online] Available from: http://www.antiuniversity.org/ABOUT. Last accessed: 20/07/1982

Johnson, R. (1988) ”Really Useful Knowledge’ 1790-1850: Memories for Education in the 1980s’. In Tom Lovett (ed.) Radical Approaches to Adult Education: A Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 3 – 35

Kasmire, S. (1996) The Myth of Mondragon: Co-operatives, Politics and Working-class Life in a Basque Town. New York: State University of New York Press

Lucas Aerospace Combine Shop Stewards Committee (1976) Corporate Plan: A Contingency Strategy as a Positive Alternative to Recession and Redundancies. [Online] Available from: http://lucasplan.org.uk/more-about-the-lucas-plan/. Last accessed: 29/11/2016

MacGilvray, E. (2010) ‘Dewey’s Public’. Contemporary Pragmatism 7(1), pp. 31 – 47

Marcus, D. (2012) ‘The Horizontalists’. Dissent. [Online] Available from: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-horizontalists. Last accessed: 29/11/2016

McGettigan, A. (2013) The Great University Gamble: Money, Markets and the Future of Higher Education. London: Pluto Press

McGettigan, A. (2015) The Treasury View of HE: Variable Human Capital Investment. PERC Papers 6. [Online] Available from: https://www.gold.ac.uk/media/documents-by-section/departments/politics-and-international-relations/PERC-6—McGettigan-and-HE-and-Human-Capital-FINAL-1.pdf. Last accessed 06/09/2016

Mirowski, P. (2013) Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown. London: Verso

Murray, C., McAlpine, R., Pollock, A and Ramsay, A. (2013) The Democratic University: A Proposal for University Governance for the Common Weal. [Online] Available from: http://reidfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Democratic-Universities.pdf. Last accessed: 29/11/2016

Neary, M. and Winn, J. (2016) Beyond Public and Private: A Framework for Co-operative Education. [Online] Available from: http://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/23051/. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

Negt, O. and Kluge, A. (1993) Public Sphere and Experience Toward an Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere. London: University of Minnesota Press.

Ralston, S. (2010). ‘Can Pragmatists be Institutionalists? John Dewey Joins the Non-ideal/Ideal Theory Debate’. Human Studies 33(1), pp. 65 – 84

Ridley-Duff, R. (2011) Co-operative University and Business School: Developing an Institutional and Education Offer. [Online] Available from: http://josswinn.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Co-operative-University-Institutional-and-Educational-Offer-Draft-3.pdf. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

Rossiter, N. (2006) Organised Networks: Media Theory, Creative Labour, New Institutions. Rotterdam: NAi Publishers

Shalmy, S. (2016) ‘Antiuniversity Now!’. Strike! 16. [Online] Available from: http://www.antiuniversity.org/ABOUT. Last accessed 20/07/2016

Shattock, M. (2012) ‘University governance’. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 16(2), pp. 56 – 61

Sitrin, M. (2006). Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina. Oakland: AK Press

Social Science Centre (SSC) (2013) ‘An Experiment in Free, Co-operative Higher Education’. Radical Philosophy 182, pp. 66 – 67

Somerville, P. (2014) Prospects for Co-operative Higher Education. [Online] Available from: http://josswinn.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Somerville-2014-Prospects-for-cooperative-higher-education.pdf. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

Taylor, B. E., Chait, R. P. and Holland, T. P. (1996) ‘The New Work of the Nonprofit Board’ Harvard Business Review 74(6), p. 36 – 48

Thompson, E. P. (1963) The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage

Trocchi, A. (1963) A Revolutionary Proposal: Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds. [Online] Available from: http://www.notbored.org/invisible.html. Last accessed: 29/11/2016

UCU (2016) Precarious Work in Higher Education: A Snapshot of Insecure Contracts and Institutional Attitudes. [Online] Available from: https://www.ucu.org.uk/article/8154/Precarious-contracts-in-HE—institution-snapshot. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

UCU (2016b) Transparency at the Top? The Second Report of Senior Pay and Perks in UK Universities. [Online] Available from: http://www.ucu.org.uk/media/7870/transparency_at_the_top_2016/pdf/VC_pay_and_perks_FINAL_VERSION21.pdf. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

UCU (2016c) When is a Pay Rise Not a Pay Rise? [Online] Available from: https://www.ucu.org.uk/when-is-a-pay-rise-not-a-pay-rise. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

UNESCO (1992) ‘Academic Freedom and University Autonomy’. Proceedings of the International Conference 5-7 May 1992, Sinaia, Romania. Available from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0009/000927/092770eo.pdf. Last accessed: 29/11/2016

Undy, R. (2013) Trade Union Organisation: 1945 to 1995. Britain at Work: Voices from the Workplace 1945-1995. [Online] Available from: http://www.unionhistory.info/britainatwork/narrativedisplay.php?type=tradeunionorganisation. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

The University for Strategic Optimism (UfSO) (2011) Undressing the Academy: The Student Handjob. London: Minor Compositions

Watermeyer, R. (2014) ‘Impact in the REF: Issues and Obstacles’. Studies in Higher Education 41(2), pp. 199-214

Waugh, C. (2009) ”Plebs’: The Lost Legacy of Independent Working-class Education’. Post-16 Educator (Occasional Publication)

Waugh, C. (2016) ‘From Chartism to Labourism’. Post-16 Educator 84, pp. 18 – 20

Winn, J. (2015) ‘The Co-operative University: Labour, Property and Pedagogy’. Power and Education 7(1), pp. 31 – 55

Woodin, T. (2015) ‘An Introduction to Co-operative Education in the Past and Present’, in Woodin, T. (ed.) Co-operation, Learning and Co-operative Values. London: Routledge, pp. 1 – 15

Wright, C. F. (2011) What Role for Trade Unions in Future Workplace Negotiations? [Online] Available from: http://www.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=3544. Last accessed: 20/07/2016

Yeo, S. (2015) ‘The Cooperative University? Transforming Higher Education’, in Woodin, T. (ed.) Co-operation, Learning and Co-operative Values. London: Routledge, pp 131 – 147